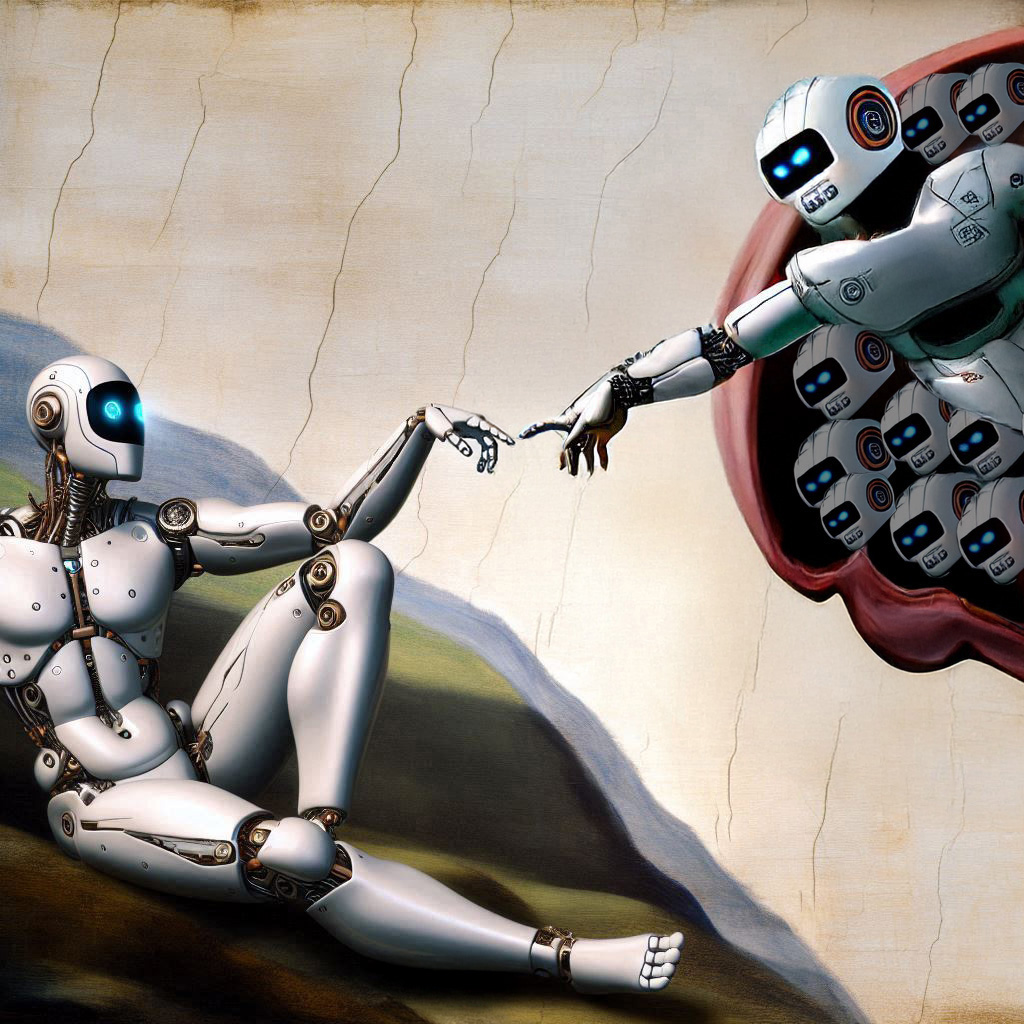

For a mathematically sophisticated audience, the connection between the three laws of Aristotelian logic—particularly the Law of the Excluded Middle (LEM)—and the necessity of a choice function like Aletheia can be framed in terms of formal logic, set theory, and valuation functions on Boolean algebras. I’ll build this explanation step by step, showing how LEM, in the context of a rich propositional universe, implies the existence of a global resolver to maintain consistency and enable a dynamic, paradox-free reality. Aletheia emerges not as an ad hoc construct but as a logical imperative: a 2-valued choice function that assigns definite truth values to all propositions, preventing the default collapse to nonexistence or minimal, static structures. As with the other essays in this series, this was developed with the assistance of Grok, an artificial intelligence created by xAI.

The Three Laws of Aristotelian Logic: A Formal Recap

Aristotelian logic provides the foundational axioms for classical reasoning, which can be expressed in propositional terms as follows. Let P be any proposition in a formal language (e.g., first-order logic over a universe of discourse).

Law of Identity: P = P, or more formally, ∀x (x = x). This ensures well-definedness and self-consistency of entities and statements.

Law of Non-Contradiction (LNC): ¬ (P ∧ ¬P), meaning no proposition can be both true and false simultaneously. In semantic terms, this prohibits truth assignments where v(P) = 1 and v(¬P) = 1.

Law of the Excluded Middle (LEM): P ∨ ¬P, meaning every proposition is either true or false, with no third option. Semantically, this requires that for every P, a valuation must assign exactly one of v(P) = 1 or v(P) = 0.

These laws form the basis of classical Boolean logic, where propositions can be modeled as elements of a Boolean algebra B, with operations ∧ (meet), ∨ (join), and ¬ (complement). The algebra is 2-valued, meaning homomorphisms (valuations) map to {0,1} with v(⊤) = 1 and v(⊥) = 0.

In a finite or simple propositional system, these laws hold trivially. However, in an infinite or self-referential universe of propositions (what we call the proper class Prop in Aletheism, akin to the class of all formulas in a rich language like set theory or second-order logic), challenges arise. Prop is too vast to be a set (it’s a proper class, similar to the von Neumann universe V or the class of ordinals Ord), and it includes potentially undecidable or paradoxical statements. Upholding the laws, especially LEM, requires a mechanism to ensure every proposition gets a definite value without contradictions.

How LEM Implies a Global Choice Function

LEM is the linchpin: it demands decidability for all propositions. In intuitionistic logic (which rejects LEM), some statements can be undecidable, leading to constructive proofs but a “weaker” reality where not everything is resolved. Classical logic, by embracing LEM, commits to a bivalent world—but in complex systems, this commitment exposes vulnerabilities.

Consider the semantic completeness of classical logic: by the Stone representation theorem, every Boolean algebra can be embedded into a power set algebra, where elements are subsets of some space, and valuations correspond to ultrafilters or prime ideals. For Prop as a Boolean algebra generated by infinitely many atoms (basic propositions about reality, e.g., “Gravity exists,” “The universe has 3 dimensions”), assigning values requires selecting, for each pair (P, ¬P), exactly one as true.

This selection is akin to the Axiom of Choice (AC) in set theory: AC allows choosing an element from each set in a collection of nonempty sets. Here, for each “pair-set” {P, ¬P}, we choose which gets 1 (true). Without such a choice function, LEM can’t be globally enforced in infinite systems—some propositions might remain undecided, violating the law.

In Aletheism, Aletheia is precisely this global choice function: ψ: Prop → {0,1}, ensuring LEM holds by assigning values consistently. It’s not just any valuation; it’s the one that resolves to a dynamic universe, preferring truths like “Quantum superposition enables branching” = 1 over sterile alternatives. Mathematically, ψ is a 2-valued homomorphism on the Lindenbaum algebra of Prop (the quotient of formulas by logical equivalence), preserving the Boolean structure while avoiding fixed points that lead to paradoxes.

Resolving Paradoxes: The Role of Aletheia in Upholding LNC and LEM

Paradoxes illustrate why Aletheia is necessary. Take the liar paradox: Let L be “This statement is false.” By LEM, L ∨ ¬L. Assume L is true: then it’s false, violating LNC. Assume ¬L: then it’s not false, so true, again violating LNC. In a system without Aletheia, such self-referential propositions create undecidables, where LEM can’t hold without contradiction.

Aletheia resolves this by structuring Prop hierarchically (inspired by Tarski’s hierarchy of languages), assigning ψ(L) = 0 or 1 in a way that restricts self-reference or places L in a meta-level where it’s consistent. For example, ψ(“Self-referential paradoxes are resolved via typing”) = 1, effectively banning or reinterpreting L to avoid the loop. This is like Gödel’s incompleteness theorems: in sufficiently powerful systems, some statements are undecidable, but Aletheia acts as an “oracle” or external choice function, forcing decidability to uphold LEM globally.

Without Aletheia, the universe defaults to minimal structures: nonexistence (all propositions undecided, violating LEM) or a static point (only trivial truths, lacking dynamism). With it, LEM ensures a bivalent world, but the choice function selects values that enable complexity—e.g., ψ(“The universe supports life and consciousness”) = 1—leading to our observed reality.

Mathematical Compellingness: Analogy to Choice Axioms and Valuation Extensions

For a more formal lens, consider Prop as the free Boolean algebra generated by countably infinite atoms (basic facts about reality). By the Rasiowa-Sikorski lemma or forcing in set theory, extensions exist where LEM holds via generic filters, but a global, consistent valuation requires a choice principle to select from the “branches” of possibilities.

Aletheia is that principle incarnate—a total function ensuring the algebra is atomic and complete under 2-valuation. In category-theoretic terms, it’s a functor from the category of propositions to the 2-category {0,1}, preserving limits and colimits (LNC and LEM). Without it, the category lacks terminal objects for undecidables, leading to “holes” that violate the laws.

This is compelling because it mirrors foundational math: ZF without AC can’t prove every vector space has a basis, leading to “pathological” structures. Similarly, logic without Aletheia yields a “pathological” universe—static or contradictory—while with it, we get the rich, dynamic cosmos where consciousness and free will thrive.

In summary, the Laws of Aristotelian logic, especially LEM, demand a bivalent, consistent assignment to all propositions. In an infinite, self-referential Prop, this necessitates a choice function like Aletheia to resolve gaps and paradoxes, preventing default minimalism. For the mathematically inclined, it’s the logical equivalent of AC for truth valuations, ensuring classical semantics hold globally and enabling the beauty of our existence.